A Est del Mar Ionio il Mediterraneo è caratterizzato dalla evoluzione dell' Arco ellenico e dell' Arco di Cipro prodotti dalla subduzione in alto della zolla africana al di sotto di quella europea. Dubbia è la presenza nelle aree abissali del Mar del Levante, tra l' isola di Cipro e l' Africa, di crosta di tipo oceanico, residuo dell'apertura giurassica della Neotetide. Le due strutture arcuate, ellenica e di Cipro, rappresentano il limite tra le zolle afro-arabica ed euroasiatica; la prosecuzione verso Est di questo limite viene ipotizzata in corrispondenza del Golfo di Iskenderun con la faglia Est-anatolica

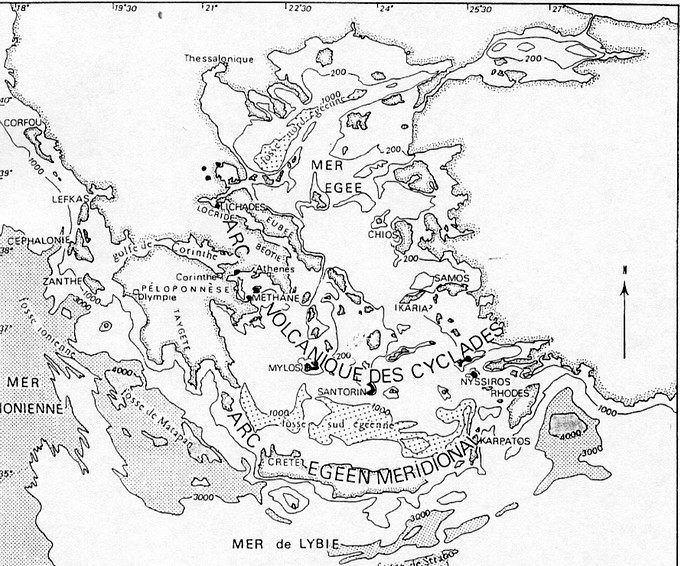

L'arco formato dalle isole Pelopponneso, Citerà, Creta, Karpatos e Rodi separa il Mar Egeo dal restante Mediterraneo orientale

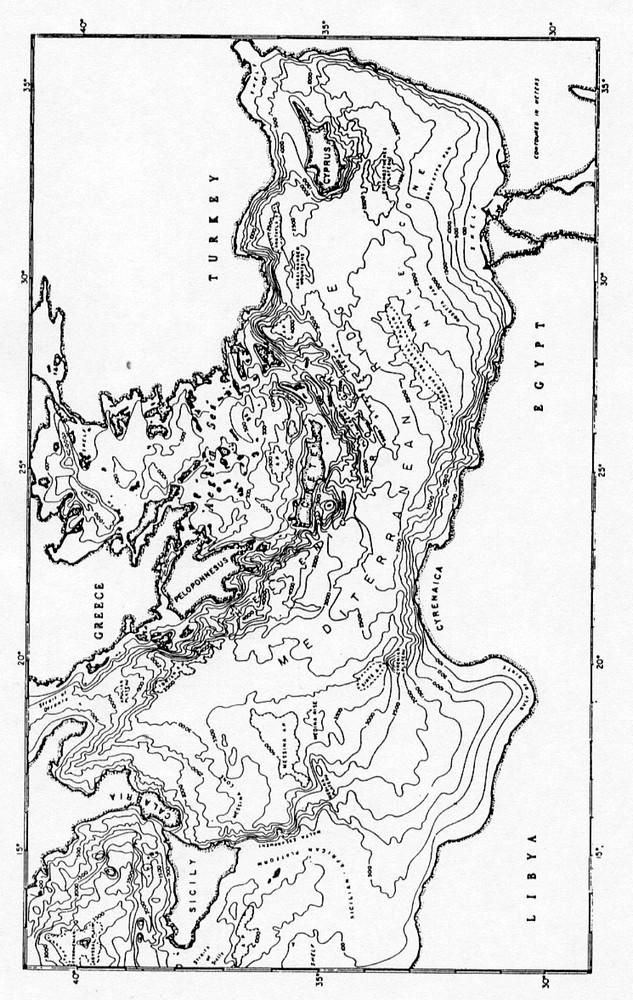

L'espressione morfologica più rilevante è costituita dalla Dorsale mediterranea: una catena ad andamento arcuato, circondata da aree abissali, che si sviluppa per 1.500 km dalla faglia di Cefalonia a Ovest sin nei pressi della Turchia a Est. parallela all'esterno all'arco sedimentario formato dalle isole meridionali dell'Egeo sopra ricordate (figg. 9.21-9.22

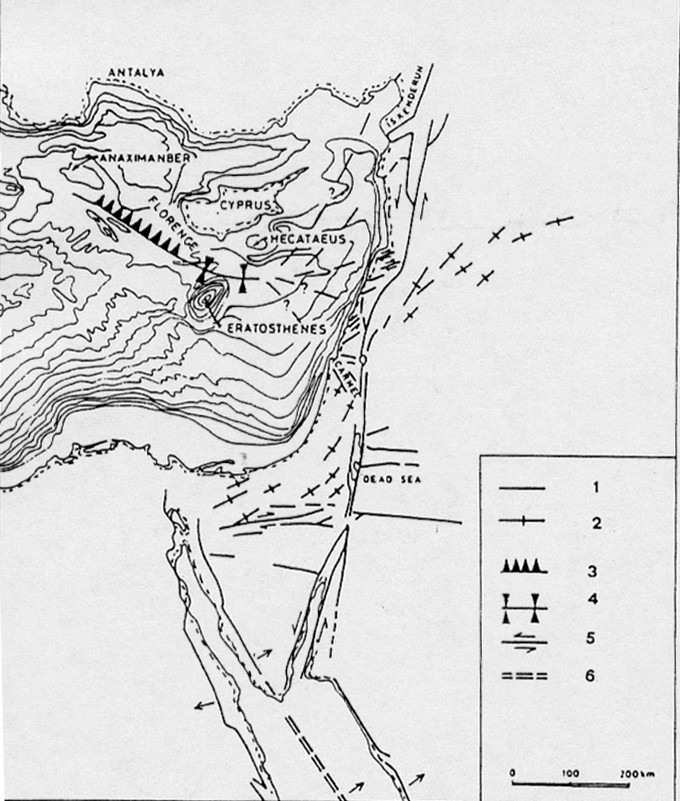

Fig. 9.21 – Carta batimetrica del Mediterraneo orientale (da Ryan e altri, in Lemoine 1978).

- -

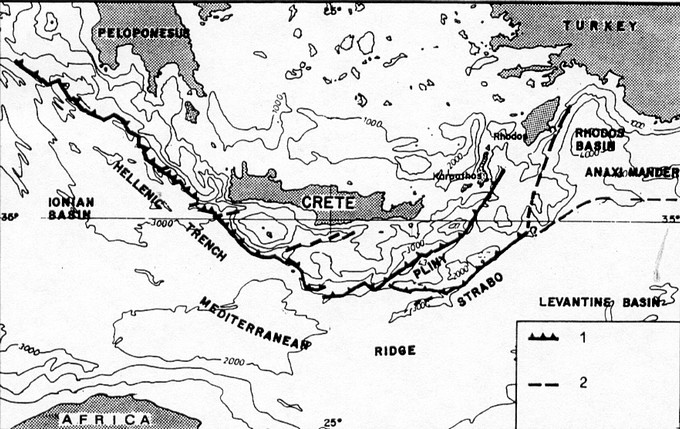

Fig. 9.22 – Principali elementi tettonici del Mediterraneo orientale. Legenda: 1) trench; 2) faglie.

Si tratta di un complesso di subduzione (quindi non paragonabile alle dorsali medio oceaniche) a forma arcuata, convessa rispetto all' Africa, largo dai 200 ai 300 km. È caratterizzata lungo il suo sviluppo da depressioni e zone rilevate, raggiunge le minori profondità di 1.100- 1.200 m nel tratto a direzione Est-Ovest parallelo alla costa africana, ove il piede dell' Africa è direttamente a contano con il pendio esterno della dorsale.

La dorsale è circondata a Nord, in corrispondenza del trench, e verso Sud. all'esterno della dorsale stessa, da una serie di depressioni o solchi assai profondi. Le depressioni esterne, della Sirte a Ovest e di Erodoto verso Est, ai piedi del delta del Nilo, sono strette e piatte, assai meno profonde di quelle interne.

Il trench ellenico è un complesso di depressioni che si sviluppa per una lunghezza di circa 1.000 km. Limite tra la zona in estensione posta a Nord e la zona in compressione posta a Sud. Presenta due tratti a diversa direzione; il ramo occidentale, il trench ionico, formato da segmenti a direzione N 40°-50° O di cui quello posto a NO, il bacino Matapan, è il più profondo, 5.000-5.500 m, parzialmente riempito da 500-1.000 m di sedimenti terrigeni probabilmente pleistocenici superiori. Il bacino Poseidon è quello più prossimo alla costa africana da cui dista I50 km, è il meno profondo, 3.000 m (fig. 9.24).

Il ramo orientale del trench è formato da un doppio sistema di solchi paralleli. il bacino Plinio, che circonda all'esterno le isole egee e il bacino Strabone, all'esterno del precedente e ad esso parallelo lungo circa 60 km. Sono depressioni strette con modeste coperture sedimentarie e per entrambi le profondità sono di circa 3.500-4.500m.

La sedimentazione clastica è fortemente influenzata dalla morfologia della dorsale; infatti l'apporto sedimentario proveniente dall'Africa viene raccolto dalle depressioni esterne: il bacino di Erodoto è alimentato dalle torbiditi provenienti dal delta del Nilo e l'area libica alimenta le depressioni della Sirte e di Messina. Le depressioni interne, del trench, sono invece alimentate da Nord, dall'Europa. essendo preclusa l'alimentazione da Sud per l'ostacolo costituito dalla presenza del rilievo della dorsale. La maggior pane dei sedimenti “europei" (il delta del Danubio) però viene intrappolata o nel Mar Nero o dal bacino di retroarco costituito dal Mar Egeo per cui l'apporto a questi bacini è assai scarso.

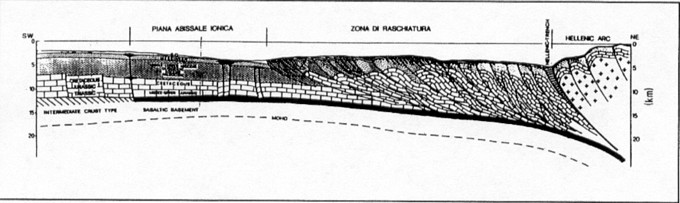

Fig. 9.23 – Sezione geologica dell’Arco ellenico dall’estremità meridionale del Pelopponneso verso SO sino alla piana abissale ionica e alla scarpata della Sirte (da Finetti 1982).

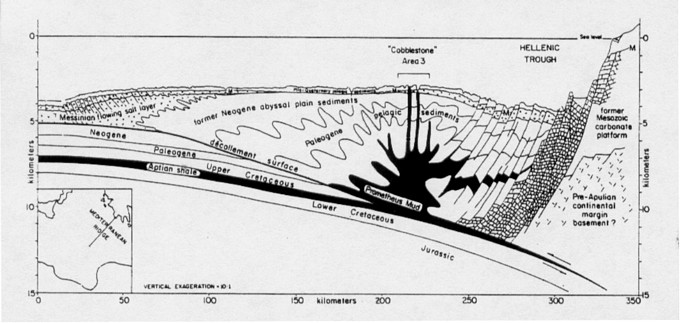

La superficie della dorsale è caratterizzata da una morfologia particolare, a cobblestone, costituita da numerose depressioni profonde da 50 a 500 m e da uno a qualche chilometro di lunghezza, parallele all'asse della dorsale, prodotte da fenomeni di dissoluzione sottomarina del sale messiniano presente al di sotto di modesti spessori di sedimenti plio-quaternari. Forme positive alte dalla decina alle centinaia di metri e diametro di qualche chilometro, sono legate a diapiri di fango (muddiapir) composti di brecce caotiche con matrice pelitica abbondante (matrix supponed) (fig. 9.24).

Fig. 9.24 - Sezione geologica della Dorsale mediterranea e del prisma di accrezione dell’Arco ellenico. Il Prometheus mud (brecce caotiche con matrice) è originato da scollamenti a tetto dei sedimenti trascinati in subduzione che risalgono verso la superficie perforando gli strati soprastanti. Il piano basale taglia livelli stratigrafici via via più profondi andando verso l’arco. Il trough ellenico è un bacino di avanarco formato da rocce carbonate mesozoiche fagliate e ribassate (da Ryan e altri, 1982).

Il movimento d'insieme dell'arco ellenico in rapporto all' Africa è da NE verso SO per cui risulta perpendicolare al ramo ionico del fronte di subduzione, mentre è quasi parallelo al ramo orientale.

L' Arco di Cipro si sviluppa a oriente dell'Arco ellenico ed è anch'esso legato alla subduzione della zolla africana. È una delle zone meno conosciute del Mediterraneo (fig. 9.25).

Qui la subduzione, per le differenze presentate dalla zolla sottoscorrente da zona a zona, è però in atto solo nel tratto occidentale dell'arco, mentre a Sud si è già verificata e ad Ovest sono presenti solo deformazioni.

L'arco si sviluppa dai seamuont di Anassinandro ad Ovest alla costa asiatica del Mar di Levante ed è formato da falde connesse all' orogenesi dei Tauridi. All'interno, tra l'arco e la Turchia. si sviluppano due bacini, di Amalia e di Adana, in posizione strutturale simile al Mar di Creta.

Il bacino di Antalia, a NO di Cipro, è profondo 2.400-2.600 m, regolato da sistemi di faglie dirette, attive dal Messiniano-Pliocene.

I sedimenti plio-quaternari, posti al di sopra delle evaporiti messiniane sono potenti da 500 a 1000

m; le evaporiti nell'adiacente dorsale danno luogo a morfologia a cobblestone.

Nella zona centrale dell'arco, all'esterno del trench, si trova il seamount di Eratostene che rappresenta una delle forme rilevate maggiori. caratterizzata anche da forte anomalie magnetiche

È un blocco di circa 100 km di diametro, che si eleva 1.500 m rispetto alle aree circostaziali, è separato dall'isola di Cipro da un graben lungo 80 km. Si tratta probabilmente di una microzolla connessa alle fasi dell'apertura oceanica mesozoica, troppo grande per essere trascinata in subduzione senza fagliarsi in blocchi minori per cui è luogo di intense deformazioni e di sismicità.

I sedimenti del Delta del Nilo, il cui cono si sviluppa per circa 300 km in mare, hanno un'età che, dai dati di sondaggio. risale almeno all'Eocene. Secondo i dati geofisici i sedimenti del Mar di Levante sono mesozoici, molto più antichi di quelli presenti nel Mediterraneo occidentale e invece confrontabili con quelli del Mar Ionio.

L'evoluzione del Mar Egeo, in posizione interna e a Nord rispetto l'Arco ellenico, è strettamente legata a quella dell'arco stesso di cui ne rappresenta il bacino di retroarco.

È un'area a crosta di tipo continentale che raggiunge il minimo spessore (20 km) nel Mar di Creta e nella Fossa Nord egea; è un bacino poco evoluto in cui la litosfera e la crosta continentale hanno subito una distensione inferiore a quella del Mar Tirreno.

Fig. 9.25 – Carta morfologica e strutturale dell’Arco di Cipro (modific. da Ben Avraham e altri, 1988). Legenda: 1) faglie; 2) pieghe; 3) piano di subduzione; 4) zona di collisione; 5) faglie trasformi; 6) zona di rift.

La batimetria è caratterizzata da numerosi bacini con profondità in genere intorno ai 1.000 m. Nella parte settentrionale tra le isole di Lemnos e Samotracia è presente la fossa rettilinea del Bacino, o Solco, Nord Egeo profonda sino a 1.500 m e allungata in senso NE-SO passante verso Est ad E-D, sino a collegarsi con il Mar di Marmora. È controllata da faglie dirette con rigetti di 6-7 km, attive dal Miocene superiore all'Attuale che formano una struttura tipo graben asimmetrico con margine meridionale più ripido; lo spessore dei sedimenti post-miocenici superiore è di 3.500 m (fig. 9.26).

A Nord e para1lelo all'Arco, tra questo e l'arco vulcanico, si sviluppa il Mar di Creta, o Fossa egea, una depressione controllata anch'essa da faglie dirette, allungata in senso E-O e la cui profondità supera i 2.000 m. La sua individuazione risale al Serravalliano -Tortoniano, lo sprofondamento è recente, Messiniano-Pliocene legato all'apertura del M. Egeo.

È accertata la presenza delle evaporiti messiniane al di sotto di più di 1.000 m di sedimenti plio-quaternari. Sino al Miocene superiore l'isola di Creta è collegata alle altre isole ed emersa: un'area continentale soggetta a sollevamento e ad intensa erosione collega la Grecia alla Turchia; come

stanno a indicare i depositi clastici pre-messiniani di Creta con provenienze da Nord e le superfici

erosive coeve presenti nell'Egeo meridionale e individuate dalle indagini geofisiche. Tra 13 e 10 M.a. l'area viene interessata da tettonica distensiva con faglie dirette e sprofondamenti differenziali che segnano l'inizio dell' evoluzione dell'area come bacino di retroarco.

Nel Tortoniano si individua il Bacino cretese e a Nord il Bacino di Saros, contemporaneamente

nella Grecia si sviluppano numerosi bacini continentali e si interrompe il collegamento di terre emerse tra Grecia e Turchia. A questa fase viene collocato l'inizio della subduzione e del movimento destro lungo la faglia Nord Anatolica.

Dopo la generale regressione dovuta alla crisi di salinità, la nuova ingressione culmina nel Pliocene superiore e il mare copre le zone costiere della Grecia e gran parte delle isole.

I fenomeni distensivi vengono interrotti da un episodio compressivo al passaggio Mio/Pliocene che produce pieghe e sovrascorrimenti, più frequenti nelle zone che formano l'arco; l'episodio viene collegato all' inizio della subduzione della litosfera mediterranea.

Nel Pliocene i fenomeni distensivi danno luogo allo svilupparsi di nuovi bacini e alla subsidenza di quelli già formati: nel Bacino di Creta si ha un notevole aumento del tasso di sedimentazione.

Un aumento dell' attività tettonica si verifica tra la fine del Pliocene e il Pleistocene in coincidenza

con lo svilupparsi dell'attuale arco vulcanico formato dalle isole di Kos, Nysiros, Santorini, Antiparos, Milos, Metbana e Aegina. 11 chimismo delle vulcaniti dell'arco vulcanico indica la presenza di un piano di Benioff posto circa 150 km al di sotto dell'arco stesso. Uno degli episodi vulcanici più imponenti è la recente gigantesca esplosione freatica di Santorini accompagnata da terremoti e da un gigantesco maremoto. Avvenuta circa 3.500 anni fa. ebbe conseguenze drammatiche sulla civiltà minoica; ed è ricordata da leggende e passi biblici.

L'espansione dell'Egeo verso Sud con assottigliamento crostale è valutata in circa 40 km. In seguito all'espansione l'Arco egeo, che all'inizio era quasi rettilineo, ha assunto una forma pressoché circolare, concentrica all'arco magmatico, con centro nell'isola di Lesbo e raggio di 300 km.

La collisione continentale in ano in corrispondenza dell'arco ha praticamente bloccato il movimento tra Africa ed Europa: la zolla litosferica in subduzione continua a sprofondare nel Mantello meno denso cosicché la zona di flessura viene a migrare verso Sud inducendo la zolla egea ad estendersi.

Fig. 9.26 – Carta batimetrica del Mar Egeo. Fig. 9.26 – Carta batimetrica del Mar Egeo.

Fig. 9.27

Mediterranean geodynamics

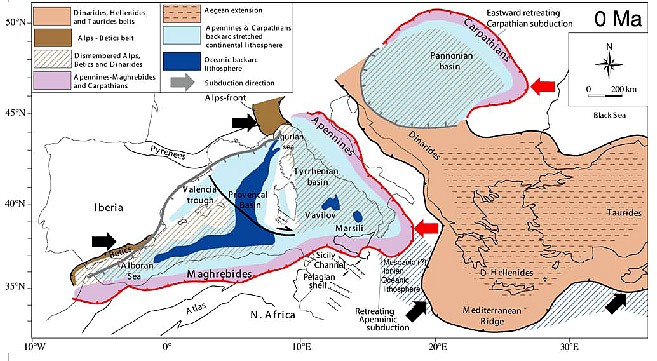

Carlo Doglioni & Eugenio Carminati

It is commonly accepted that the Mediterranean geology has been shaped by the interplay between two plates, i.e., Africa and Europe (fig. 186), and possibly smaller intervening microplates. The Mediterranean was mainly affected by rifting after the Variscan orogeny: during the Mesozoic, oceanic Tethys areas and passive continental margins developed, where widespread carbonate platforms grew up. During the late Mesozoic, the Mediterranean area was rather dominated by

subduction zones (from east to west, Cimmerian, Dinarides, Alps-Betics), which inverted the extensional regime, consuming the previously formed Tethyan oceanic lithosphere and the adjacent continental margins. The composition (i.e., oceanic or continental), density and thickness of the lithosphere inherited from the Mesozoic rift controlled the location, distribution and evolution of the later subduction zones. The shorter wavelength of the Mediterranean orogens with respect to other belts (e.g., Cordillera, Himalayas) is due to the smaller wavelength of the lithospheric anisotropies inherited from the Tethyan rift.

The Mediterranean basin was and still is the collector of sediments coming from the erosion

of the surrounding continents and orogens: the best examples are the Nile and Rhone deltas. In the past, other deltas deposited at the bottom of the Mediterranean, and their rivers were later disconnected or abandoned: an example is the Upper Oligocene- Lower Miocene Numidian Sandstone, which was supplied from Africa, deposited in the central Mediterranean basin, and partly uplifted by the Apennines accretionary prism. It is notorious also that during the Messinian eustatic low-stand, the Mediterranean dried several times, generating the salinity crisis in which

thick sequences of evaporites deposited in the basin. This episode generated a pulsating loading

oscillation in the Mediterranean, because the repetitive removal of the water should have generated significant isostatic rebound in most of the basin, particularly where it was deeper as in Ionian, in the Provençal and in the central Tyrrhenian seas. The Neogene to present direction of Africa- Europe relative motion is still under debate. Most of the reconstructions show directions of relative motion spanning between northwest to northeast. Recent space geodesy data confirm this main frame, where Africa has about 5 mm/yr of N-S component of convergence relative to Europe, but they also show that the absolute plate motions directions of both Europe and Africa are northeast oriented and not north or northwest directed as usually assumed (see the NASA data base on present

global plate motions, http://sideshow.jpl.nasa.gov:80/mbh/series.html).

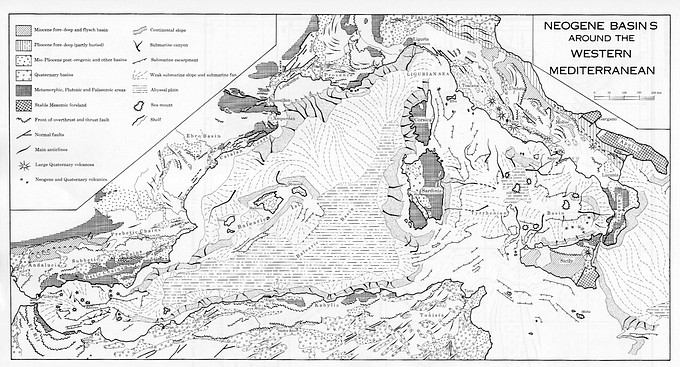

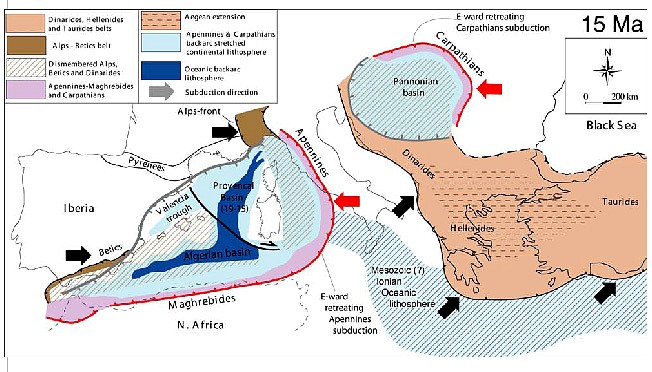

The main Cenozoic subductions of the Mediterranean are the Alps-Betics, the Apennines-Maghrebides, and the Dinarides- Hellenides-Taurides (figs. 187 - 193). Closely related to the Mediterranean geodynamics are the Carpathians subduction and the Pyrenees.

The Mediterranean orogens show two distinct signatures similar to those occurring in the opposite sides of the Pacific Ocean. High morphologic and structural elevation, double vergence, thick crust, involvement of deep crustal rocks, and shallow foredeeps characterize E or NE-directed subduction zones (Alps-Betics, Dinarides-Hellenides-Taurides). On the other hand, low morphologic and structural elevation, single vergence, thin crust, involvement of shallow rocks, deep foredeep and a widely developed backarc basin characterize W-directed subduction zones (Apennines, Carpathians). This asymmetry can be ascribed to the "W"-

Fig. 186 - NASA-Shuttle view of the central western Mediterranean.

ve to the mantle with rates of about 49 mm/y, as computed adopting the hotspots reference frame. All Mediterraean orogens show typical thrust belt geometries with imbricate fan and antiformal stack associations of thrusts. The main difference between orogens and within the single belts is the variation in depth of the basal decollement. Deeper it is, higher is the structural and morphologic elevation of the related orogen.

Extensional basins have superimposed these orogenic belts, i.e., in the western side the Valencia, Provençal, Alboran, Algerian, Tyrrhenian Basins, and in the eastern side the Aegean Basin, and to the north the Pannonian Basin.

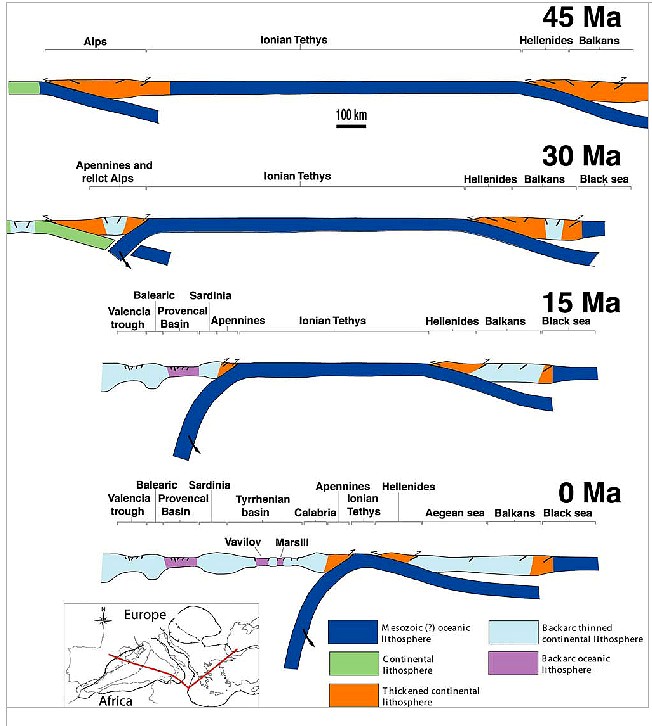

The Mediterranean can be divided into the western, central, and the eastern basins. The western Mediterranean is younger (mainly < 30 Ma) relative to the central and eastern Mediterranean areas, which are mainly relics of the Mesozoic-Cenozoic(?) Tethys.

Positive gravity anomalies occur in deep basins (e.g., Provençal, Tyrrhenian and Ionian seas) where the mantle was uplifted by rifting processes. Negative gravity anomalies rather occur along the subduction zones.

A characteristic feature of the western Mediterranean is the large variation in lithospheric and crustal thickness. The lithosphere has been thinned to less than 60 km in the basins (50-60 km in the Valencia trough, 40 km in the eastern Alboran sea, and 20-25 km in the Tyrrhenian) while it is 65-80 km thick below the continental swells (Corsica-Sardinia and Balearic Promontory). The crust mimics these differences with a thickness of 8-15 km in the basins (Valencia trough, Alboran sea,

Ligurian sea and Tyrrhenian sea) and 20-30 km underneath the swells (Balearic Promontory

and Corsica-Sardinia), as inferred by seismic and gravity data. These lateral variations in

Fig. 187 - Present geodynamic framework. There are four subduction zones with variable active rates in the Mediterranean realm: the W-directed Apennines-Maghrebides; the W-directed Carpathians; the NE-directed Dinarides-Hellenides-Taurides; the SE-directed Alps.

The Apennines-Maghrebides subduction-related backarc basin of the western Mediterranean stretched and scattered into the segmented basins most of the Alps-Betics orogen (after CARMINATI & DOGLIONI, 2004).

thickness and composition are related to the rifting process that affected the western Mediterranean, which is a coherent system of interrelated irregular troughs, mainly V-shaped, which began to develop in the Late Oligocene-Early Miocene in the westernmost parts (Alboran, Valencia, Provençal), becoming progressively younger eastward (Eastern Balearic, Algerian basins), up to the presently active E-W extension in the Tyrrhenian Sea. Heat flow data and thermal modelling show that the maximum heat flow values are encountered in the basins: 120 mW/m2 in the eastern Alboran, 90-100 mW/m2 in the Valencia trough, and more than 200 mW/m2 in the Tyrrhenian Sea. All these sub-basins appear to be genetically linked to the backarc opening related to the coeval "E"-ward rollback of the W-directed Apennines- Maghrebides subduction zone. Extreme stretching generated oceanic crust in the Provençal (20-15 Ma), Algerian (17-10), Vavilov and Marsili basins (7-0 Ma). During the 25-10 Ma time frame, the Corsica-Sardinia block rotated 60° counter clockwise. In the southern Apennines, the choking of the subduction zone with the thicker continental lithosphere of the Apulia Platform slowed the E-ward migration of the subduction hinge, whereas in the central and northern Apennines and in Calabria the subduction is still active due to the presence in the foreland of thin continental lithosphere in the Adriatic Sea, and of Mesozoic (?) oceanic lithosphere in the Ionian Sea, allowing rollback of the subduction hinge. The western Mediterranean basins tend to close both morphologically and structurally toward the southwest (Alboran Sea) and northeast (Ligurian Sea). The eastward migration of the arc associated with the W-directed subduction generated right-lateral transpression along the entire E-W-trending northern African belt (Maghrebides) and its Sicilian continuation, whereas left-lateral transtension has been described along the same trend in the backarc setting just to the north of the Africanmargin. An opposite tectonic setting can be described in the northern margin of the arc.

Subduction retreat generated calkalcaline and shoshonitic magmatic episodes particularly located in the western margins of the lithospheric boudins, later followed by alkalinetholeiitic magmas in the backarc to the west. Extension partly originated in areas previously occupied by the Alps-Betics orogen, which formed since Cretaceous due to an "E"-directed subduction of Europe and Iberia underneath the Adriatic plate and an hypothetical Mesomediterranean plate. Once restored Sardinia to its position prior to rotation, during the early Cenozoic the Alps were probably joined with the Betics in a double vergent single belt. The Western Alps, which are the forebelt of the Alps, were connected to Alpine Corsica; the Alps continued SW-ward into the Balearic promontory and Betics.

Fig. 188 - Paleogeodynamics at about 15 Ma. Note the "E"-ward vergence of both Apennines-Maghrebides trench and the backarc extensional wave. The Liguro-Provençal basin, the Valencia Trough and the North Algerian basin were almost completely opened at 10 Ma. The Dinarides subduction slowed down, due to the presence of the thick Adriatic continental lithosphere to the west, whereas to the south, the Hellenic subduction was very lively due to the presence in the footwall plate of the Ionian oceanic lithosphere.

The Carpathians migrated E-ward, generating the Pannonian backarc basin, with kinematics similar to the Apennines (after CARMINATI & DOGLIONI, 2004).

The retrobelt of the Alps, i.e., the Southern Alps, were also continuing from northern Italy toward the SW. In a double vergent orogen, the forebelt is the frontal part, synthetic to the subduction, and verging toward the subducting plate; the retrobelt is the internal part, antithetic to the subduction, and verging toward the interior of the overriding plate. The W-directed Apennines-Maghrebides subduction started along the Alps-Betics retrobelt, where oceanic and thinned continental lithosphere was occurring in the foreland to the east. In fact the subduction underneath the Apennines-Maghrebides consumed inherited Tethyan domains. The subduction and the related arc migrated "E"-ward at speed of 25-30 mm/yr.

Fig. 189 - Paleogeodynamics at about 30 Ma. The location of the subduction zones is controlled by the Mesozoic paleogeography. The Alps-Betics formed along the SE-ward dipping subduction of Europe and Iberia underneath the Adriatic and Mesomediterranean plates.

The Apennines developed along the Alps-Betics retrobelt, where oceanic or thinned pre-existing continental lithosphere was present to the east. Similarly, the Carpathians started to develop along the Dinarides retrobelt (i.e., the Balkans). The fronts of the Alps-Betics orogen are cross-cut by the Apennines-related subduction backarc extension (after CARMINATI & DOGLIONI, 2004)

Fig. 190 - Paleogeodynamics at about 45 Ma. The Alps were a continuous belt into the Betics down to the Gibraltar consuming an ocean located relatively to the west (after CARMINATI & DOGLIONI, 2004).

Fig. 191 - Main tectonic features of the Mediterranean realm, which has been shaped during the last 45 Ma by a number of subduction zones and related belts: the double vergent Alps-Betics; the single "E"-vergent Apennines-Maghrebides and the related western Mediterranean backarc basin; the double vergent Dinarides-Hellenides-Taurides and related Aegean extension; the single "E"-vergent Carpathians and the related Pannonian backarc basin; the double vergent Pyrenees (after CARMINATI & DOGLIONI, 2004).

Apennines-Maghrebides consumed inherited Tethyan domains. The subduction and the related arc migrated "E"-ward at speed of 25-30 mm/yr.

The western Late Oligocene-Early Miocene basins of the Mediterranean nucleated both within the Betics orogen (e.g., Alboran sea) and in its foreland (Valencia and Provençal troughs). At that time the N40°-70° direction of grabens was oblique to the coexisting N60°- 80°-trending Betics orogen, indicating its structural independence from the Betics orogeny. Thus, as the extension cross-cuts the orogen and developed also well outside the thrust belt front, the westernmost basins of the Mediterranean developed independently from the Alps-Betics orogen, being rather related to the innermost early phases of the backarc extension in the hangingwall of the Apennines-Maghrebides subduction. In contrast with the "E"-ward migrating extensional basins and following the "E"-ward retreat of the Apennines subduction, the Betics-Balearic thrust front was migrating "W"-ward, producing interference or inversion structures. The part of the Alps-Betics orogen was located in the area of the Apennines-Maghrebides backarc basin, it has been disarticulated and spread-out into the western Mediterranean (e.g.,the metamorphic slices of Kabylie in NAlgeria, and Calabria in S-Italy). Alpine type basement rocks have been dragged in the Tyrrhenian Sea. Similarly, boudinage of the pre-existing Alps and Dinarides orogens occurred in the Pannonian basin, which is the Oligocene to Present backarc basin related to the coeval Eward retreating, W-directed Carpathians subduction zone. In the Pannonian basin, the extension isolated boudins of continental lithosphere previously thickened by the earlier Dinarides orogen, like the Apuseni Mountains that separate the Pannonian basin s.s. from the Transylvanian basin to the east. The western Mediterranean backarc setting is comparable with Atlantic and western Pacific backarc basins that show similar large-scale lithospheric boudinage, where parts of earlier orogens have been scattered in the backarc area, like the Central America Cordillera relicts that are dispersed in the Caribbean domain.

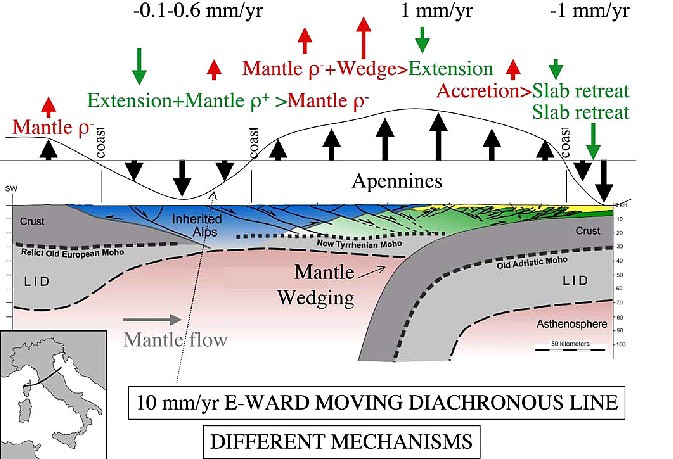

The Apennines accretionary prism formed in sequence at the front of the pre-existing Alpine retrobelt, and therefore the central western Apennines contain also the inherited Alpine orogen of Cretaceous to Miocene age. There has probably been a temporary coexistence of the opposite subductions during the Late Oligocene - Early Miocene. Structural and geophysical data support the presence of an eastward migrating asthenospheric wedge at the subduction hinge of the retreating Adriatic plate. The flip of the subduction, from the Alpine E-directed to the Apennines W-directed subduction could have been recorded by the drastic increase of the subsidence rates in the Apennines foredeep during the Late Oligocene - Early Miocene. In fact, west-directed subduction zones such as the Apennines show foredeep subsidence rates up to 10 times faster (>1 mm/yr) than to the Alpine foredeeps. The flip of the subduction could also be highlighted by the larger involvement of the crust during the earlier Alpine stages with respect to the Apennines decollements that mainly deformed the sedimentary cover and the phyllitic basement. It has been demonstrated that the load of the Apennines and Carpathians orogens is not sufficient to generate the 4-8 km deep Pliocene-Pleistocene foredeep basins, and a mantle origin has been proposed as mechanism (slab pull and/or E-ward mantle flow).

Paradoxically the extension determining most of the western Mediterranean developed in a

context of relative convergence between Africa and Europe. However it appears that the maximum amount of North-South Africa/Europe relative motion at the Tunisia longitude was about 135 km in the last 23 Ma, more than five times slower with respect to the eastward migration of the Apennines arc which moved eastward more than 700 km during the last 23 Ma. Therefore the eastward migration of the Apennines-Maghrebides arc is not a consequence of the relative N-S relative convergence between Africa and Europe, but it is rather a consequence of the Apennines- Maghrebides subduction rollback, which was generated either by slab pull and/or the "E"-ward mantle flow relative to the lithosphere

Fig. 193 - During the last 45 Ma, the evolution of the Mediterranean along the trace shown in the map is the result of three main subduction zones: i.e., the early E-directed Alpine subduction; the Apennines subduction switch along the Alps retrobelt; the Dinarides-Hellenides subduction. The last two slabs retreated at the expenses of the inherited Tethyan Mesozoic oceanic or thinned continental lithosphere. In their respective hangingwalls, a few rifts formed as backarc basins, progressively younger toward the subduction hinges. The slab is steeper underneath the Apennines, possibly due to the W-ward drift of the lithosphere relative to the mantle (after CARMINATI & DOGLIONI, 2004).

detected in the hotspot reference frame. The development of the western Mediterranean occurred mainly after the terminal convergence in the Pyrenees at about 20 Ma, which formed due to the collision between Europe and the Late Cretaceous-Early Tertiary counter-clockwise rotating Iberia contemporaneously to the opening of the Biscay Basin In northern Africa, south of the Maghrebides (and related Algerian Tell and Moroccan Riff the Atlas mountains represent an intraplate inversion structure, where extensional (NNEtrending)

and left-lateral (about E-W-trending) transtensional Mesozoic intercontinental rifts were later buckled and squeezed by Cenozoic compression and right-lateral transpression, in the foreland of the Apennines-Maghrebides subduction zone. This is also indicated by the thicker Mesozoic sequences in the Atlas ranges with respect to the adjacent not deformed mesetas.

Fig. 194 - Cross-section of the Northern Apennines. The Alps are interpreted as a boudinaged relict stretched in the Tyrrhenian Sea and western Northern Apennines. The retrobelt of the Alps is considered the prolongation of the Southern Alps. The numbers are interpreted vertical and horizontal velocity rates. It shows how in the same tectonic system different geodynamic mechanisms may concur. Green and red arrows indicate subsidence and uplift mechanisms respectively. Modified after CARMINATI et alii (2004b).

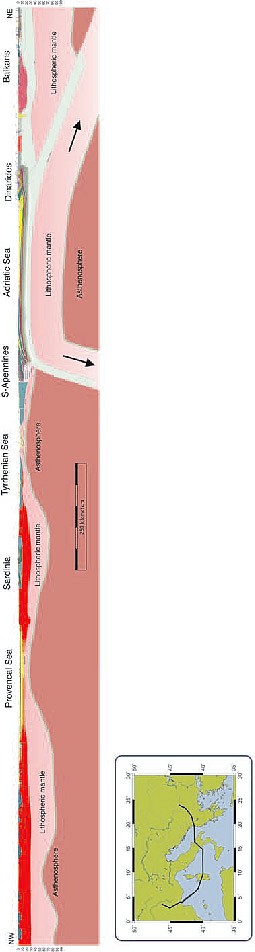

Fig. 192 - Transmed transect III. Modified after CARMINATI et alii (2004a).

|